When Claude Gellée arrived as a boy in Rome from his native Lorraine, perhaps to serve as a pastry cook, landscape painting was already a recognised speciality. Claude, however, was to surpass all previous practitioners. His poetic reinventions of a Golden Age, appealing to a cultivated aristocratic clientele, were assembled in the studio from drawings made out-of-doors in Rome and the surrounding countryside and in the Bay of Naples. Claude's influence became all-pervasive, most of all in eighteenth-century England, where it affected not only painting and collecting but the very ways in which real landscape was viewed and artificial parkland constructed. Like many of Claude's pictures, Seaport with the Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba was conceived as one of a pair; its companion, Landscape with the Marriage of Isaac and Rebekah (“The Mill”), is also at the National Gallery. The pair was commissioned by Camillo Pamphilj, nephew of Pope Innocent X. Before the exceptionally large canvases had been completed, Pamphilj renounced his cardinal's hat to marry and was expelled from Rome in disgrace; the paintings were finished for the Duc de Bouillon, French general of the papal armies. Both pieces relate (through inscriptions, our only clues to their subjects) to stories from the Old Testament—thought at the time to be especially suitable for the pictorial decoration of cardinals' palaces—on the theme of love, or esteem, between men and women and the recounting fateful journeys. While most contemporary churchmen would have interpreted the tales as symbolic of Christ's union with the Church, Pamphilj may have wished to refer covertly to his own love for Olimpia Aldobrandini.The way in which he incorporated the sun into his work was Claude's greatest early innovation. Exactly half-way up the canvas in this stateliest of his seaport compositions, it is the basis of its pictorial unity, all the colors and tones adjusted in relation to it. The boy sprawling on the quay-side shields his eyes from the sun’s dazzle, and its rays gild the rounded edges of the fluted column and Corinthian capital beside him. Claude's palm and fingerprints can be seen in many places in the sky, where he smoothed transitions from one passage to the next.

Seaport with the Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba

oil on canvas • 148 x 194 cm

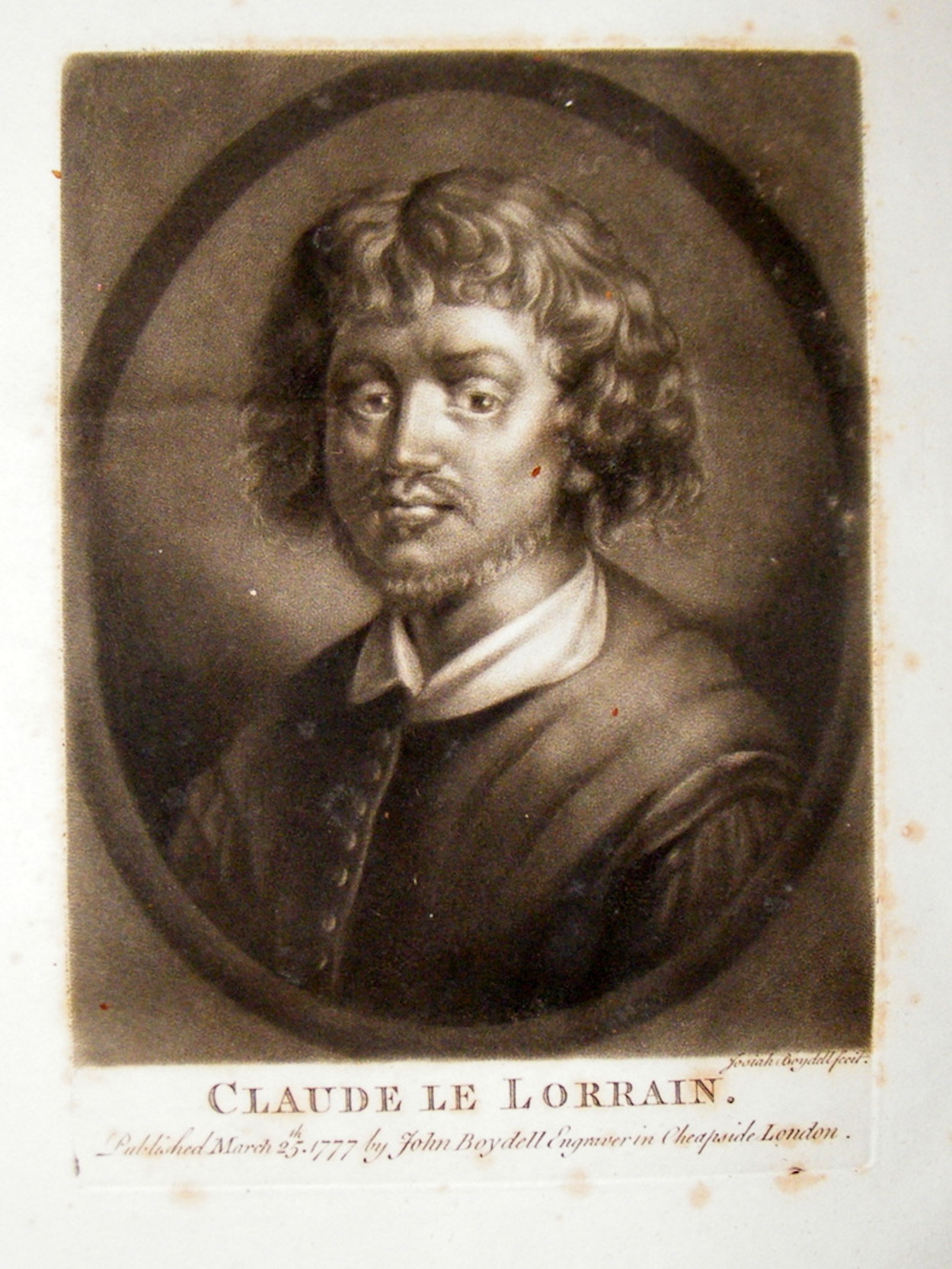

Claude Lorrain

Claude Lorrain