A water drop in a drought is a blessing, but the same drop in a flood is a curse. What’s the nature of goodness, and how is evil determinable? Whenever asked about Lisbon, I always remark on the uniqueness of its light. Sunlight is held and spread like golden velvet, almost touchable, a succulent beam streaming through vast squares, shattered amid river reflections or by old windows, fading through tight ancient streets, until the shadowy alleys embrace darkness. November first, a holy Christian day, 1755: Lisbon trembles upon what became known as the Great Lisbon earthquake, a destructive earthquake followed by a tsunami. The disaster was of such epic proportions that it became a matter of debate for a philosophical theme named “the problem of evil”, engaging such personalities as Rousseau, Kant, Goethe… but particularly Voltaire, who aimed to discredit Leibniz’s vision of “The Best of all Possible Worlds”. Those thinking about the problem of evil ask: “How can there be evil if there’s also a good omnipotent God?”.

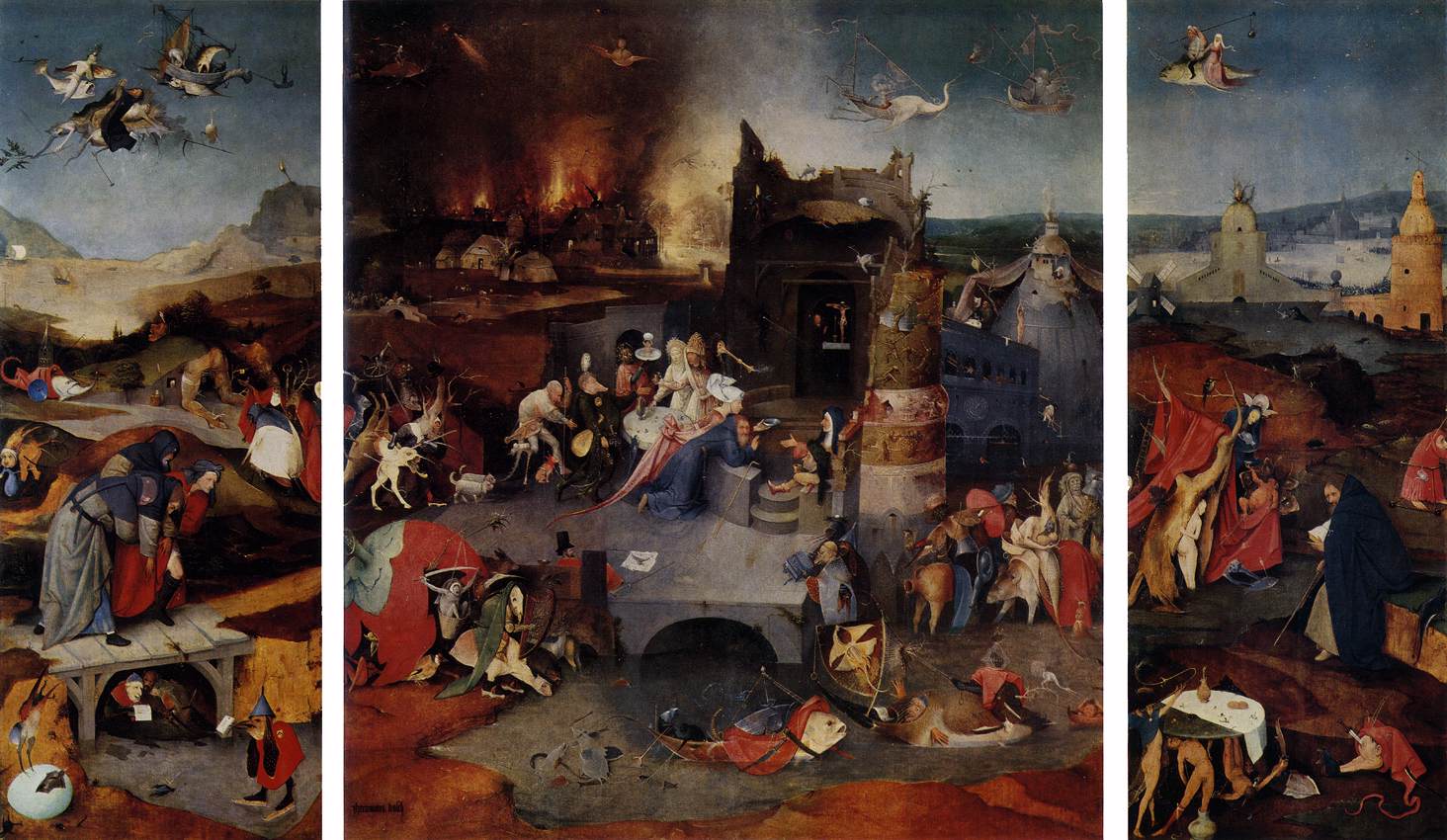

Leibniz responded by saying that this world is the best possible one, so evil is really not that evil, just the minimum necessary in a “not-so-bad-after-all” world. Voltaire didn't buy it and neither do I. I regard the question pretty much as Lisbon does.If Lisbon’s light wasn't metaphorical enough, let me show you today’s painting - my favourite in town. Hieronymus Bosch left few clues about his life, but his work has been highly studied. Fond of the occult, it's known that Bosch joined the Brotherhood of Our Lady, a local religious confraternity, becoming an elite member. Thus his strong connection to religious themes, with an alternative approach that tilted towards the grotesque, satirising the sins of religious orders and exposing bad conduct. I really admire in Bosch his sophisticated vision of good and evil. His usual representation of an owl, for example, depicts in the same element the viciousness of a night creature, but also the symbol of wisdom. It is almost as if evil was already present in Creation.

The book of Genesis doesn't say animals were created differently than they are today, where animals eat each other. “God saw that it was good”, being a good cat is being a good hunter: a mouse killer. Personally, I look up to no Deity for a moral code. That what can be seen as good is highly mutable and dances with the circumstances. Logic, love, empathy and a skeptical inquiring mind-set is all it takes to create a moral code based on our impact towards others. Epicurus, the ancient greek philosopher, designed this paradox:“God either wishes to take away evils, and is unable; or He is able, and is unwilling; If He is willing and is unable, He is feeble, which is not in accordance with the character of God; if He is able and unwilling, He is envious, which is equally at variance with God; if He is neither willing nor able, He is both envious and feeble, and therefore not God; if He is both willing and able, which alone is suitable to God, from what source then are evils? Or why does He not remove them?”. So, should this still be a time for Religious Motivations? My condolences to the victims of 9/11, it has been 15 years since the events that won't be forgotten.

- Artur Deus Dionisio

Hieronymus Bosch

Hieronymus Bosch