The Beatles’ album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was an icon in an age known for catapulting psychedelics into the mainstream. Everybody wanted to join “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” so drugs became a more prevalent part of artistic culture than ever before. But, of course, drugs were having an impact on culture long before the 1960s.

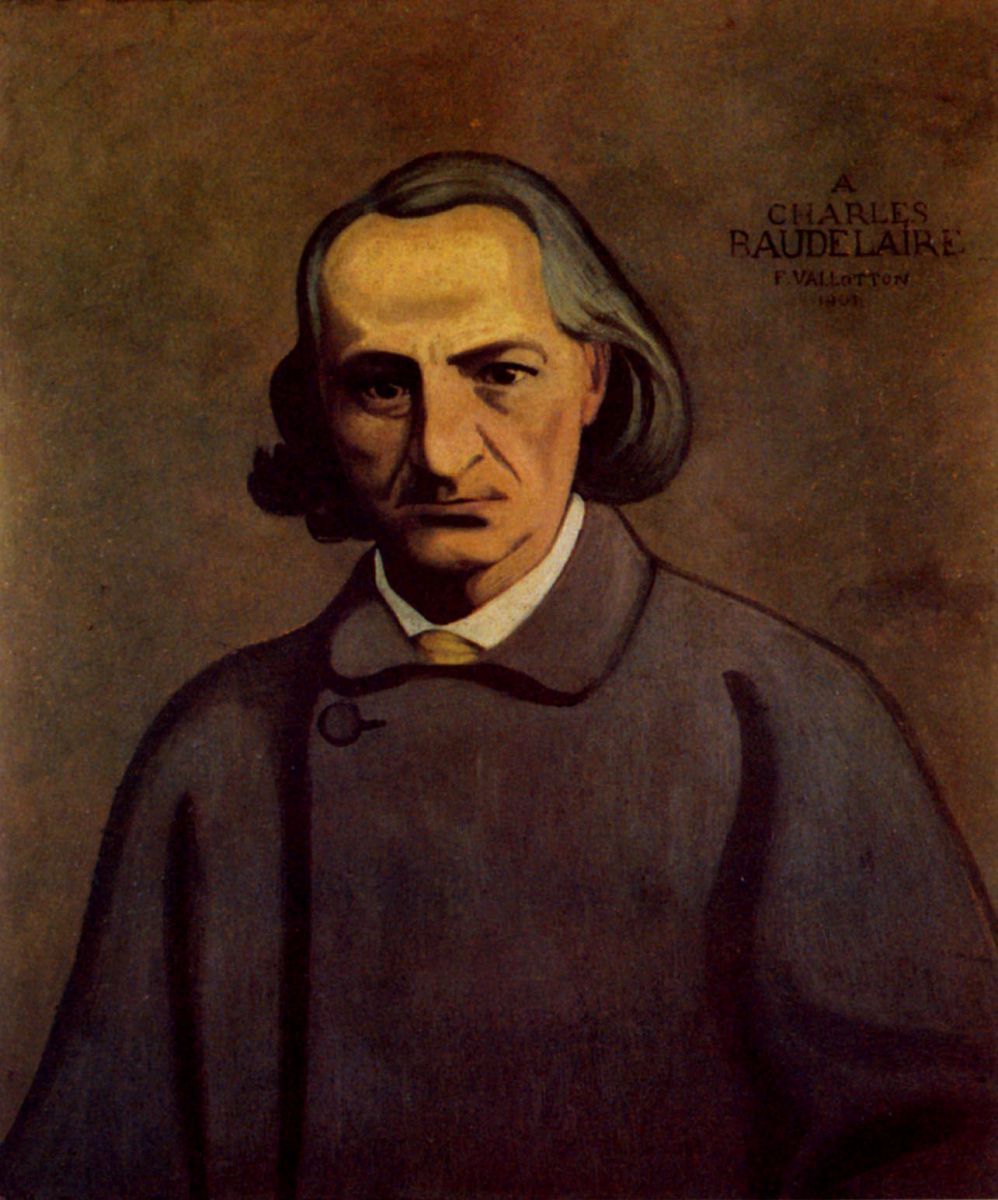

Salvador Dalí once famously said, “I don’t do drugs. I am drugs.” This was not a “say-no-to-drugs commercial” but rather an exaltation. He was, in a way, claiming that his work itself could induce the alternative states provoked by drugs. Baudelaire, the decadent author portrayed in today’s artwork, theorized in his book Les Paradis Artificiels how drugs might help create an ideal world.

Other thinkers and artists were aware of the power of drugs. Nietzsche took opium as a treatment for migraines and nausea; scholars debate on how it might have inspired his work. Jean-Paul Sartre injected mescaline to better understand consciousness - an event followed by weeks of paranoia as he thought he was being pursued by giant lobsters! And absinthe was hugely popular in bohemian France: Degas, Gauguin, van Gogh, Lautrec, Baudelaire, and many others drunk it as a source of inspiration.

Plato himself attended the Eleusinian Mysteries - mystical events held in ancient Greece - where the participants drank a psychotropic potion named kykeon. Plato remarked about his experiments: “being permitted as initiates to the sight of perfect and simple and calm and happy apparitions, which we saw in the pure light, being ourselves pure and not entombed in this which we carry about with us and call the body, in which we are imprisoned.” That might be the origin the mind\body dualism, a structural argument that has been used used from Christianity to Descartes’ famous “I think therefore I am.” The prevalence of hallucinogens and narcotics is such that we might even question if drugs are perhaps a cornerstone of Western philosophy.

Norman Ohler’s book, Der Totale Rausch, a discusses the use of drugs during Nazi Germany, where methamphetamines use was massive. Pervitin, a methamphetamine, was consumed both by housewives and workers to endure the day - it was sold without any medical prescription. Between 1925 and 1930, Germany alone produced 40% of the world’s morphine.

But what about all the drugs we are taking today? Sure, not everybody is hooked on cocaine, but what about antidepressants, alcohol, and caffeine? Isn’t it strange how it so socially accepted over other light drugs?

I have a bit of a perverted curiosity, although I know implementing it would be dangerous: What if we let athletes take performance-enhancing drug and compete, so we could see just how far the human body can (artificially) go? Of course, this could be disastrous, but it does make you wonder...

- Artur Deus Dionisio

Félix Vallotton

Félix Vallotton