Dear DailyArt users, if you need artsy calendars for 2020 we have something for you! Check what you can buy on our new DailyArt online shop: Women Artists Monthly Wall Calendar, Masterpieces Monthly Wall Calendar and Weekly Desk Calendar, with beautiful masterpieces and short stories about them. We ship worldwide!

We continue our special month with the Caravaggio & Bernini exhibition at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, on view until January 20th, 2020. It's a real must-see, don't miss it! And if you can't make it to Vienna, read us on Sundays this month. : )

Although this Medusa is not mentioned in the earliest records of the sculptor’s work by Filippo Baldinucci and Domenico Bernini, the style, the daring with which the wildly writhing snakes on the figure’s head are carved, and the extremely clever concetto of the marble ("an awful pun") strongly suggest Bernini’s authorship.

The monstrous Medusa’s hair was a nest of serpents; those who looked at her would turn to stone. Perseus was able to escape her fatal powers by looking at her only indirectly, through the highly polished metal of his shield. Protected like this, Perseus decapitated Medusa in her sleep.

Bernini’s bust depicts Medusa’s rigid head before Perseus has put an end to her. The artist was inspired here not so much by Caravaggio’s illusionistic shield with Medusa's horrified likeness itself, as by the poetic treatment of that depiction in Giambattista Marino’s La Galeria (1619). The poet had used Medusa’s own words to implicitly invite sculptors to take her petrifaction as their subject: "I know not if I was sculpted by mortal chisel, or if by gazing into a clear glass my own glance made me so."

Bernini’s response to Marino is a demonstration of technical virtuosity and vitality, designed to evoke the viewers’ stupefaction (stupore) so that they are likewise "petrified." He turned his chisel to another line in Marino’s sonnet, in which Medusa warns the reader that a glance even from a marble version of her face—a work of art—would be able to turn the viewer to stone. Thus, Bernini created (for those in the know, at least) a paragone (comparison) between two sister arts: ut scultura poesis (as is sculpture so is poetry): poetry as speaking sculpture, and sculpture as silent poetry.

The Italian author and theoretician Cesare Ripa associated Medusa with jealousy and her snakes with the evil thoughts that come from a wicked heart; the sculpture can therefore also be read as an emblem of silencing jealous gossip and thus the victory of wise discretion. The significance for Bernini may even have been more immediate and personal in reference to the abrupt end in 1638 of his passionate affair with Costanza Piccolomini (Bonarelli), whose features are clearly akin to the Medusa’s.

- FS

P.S. See the five most famous head of Medusa paintings in art history here. Beautiful and scary at the same time!

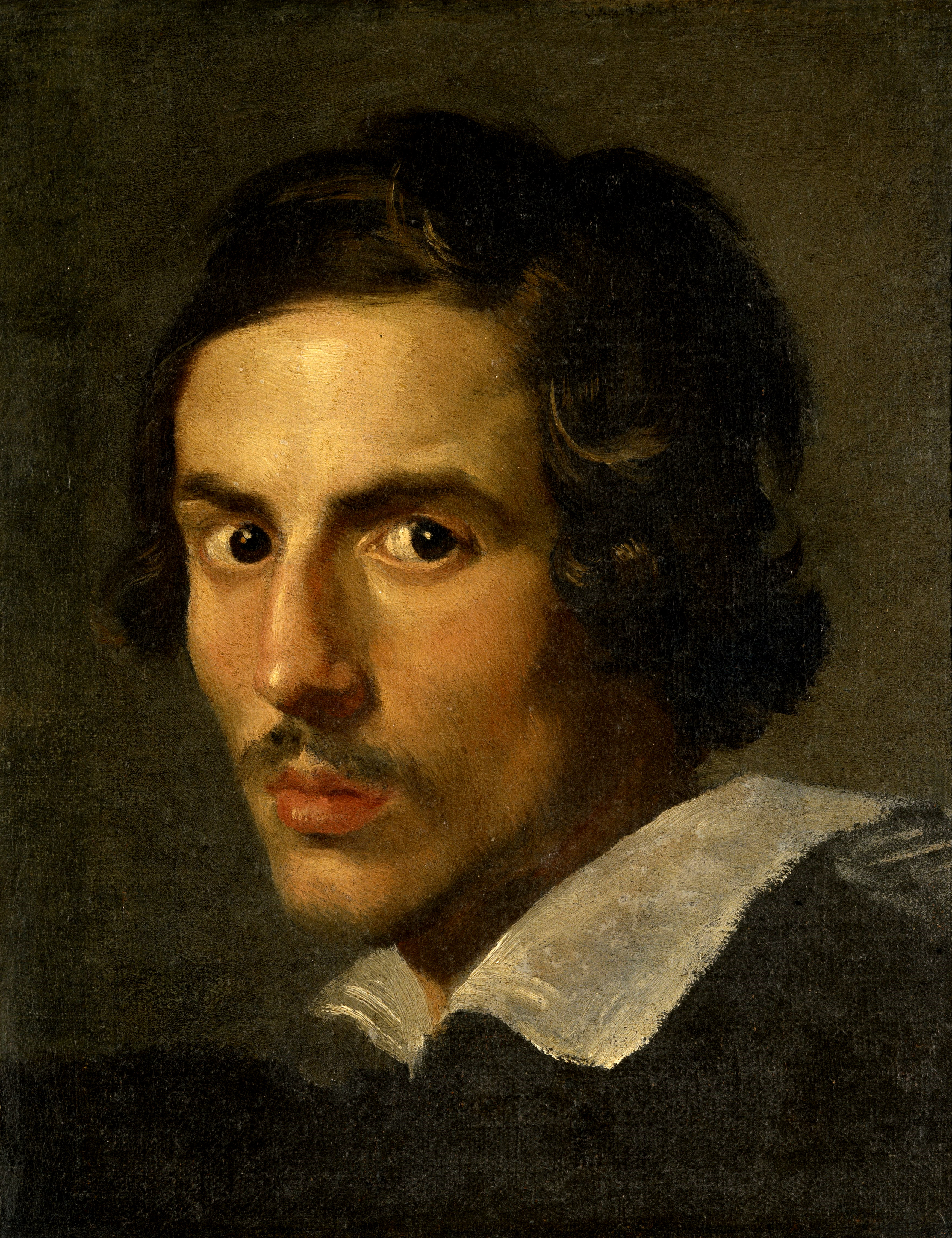

Gianlorenzo Bernini

Gianlorenzo Bernini