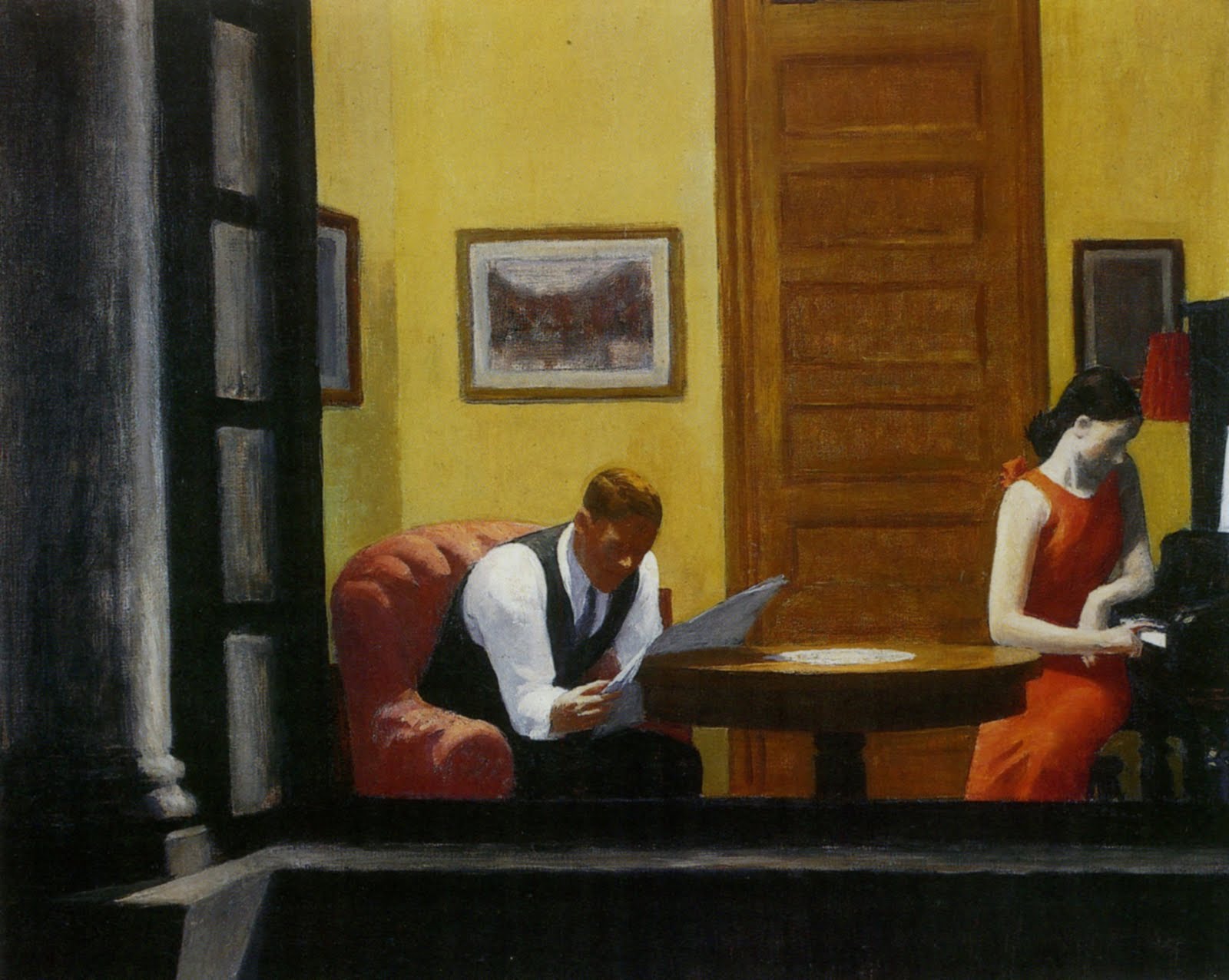

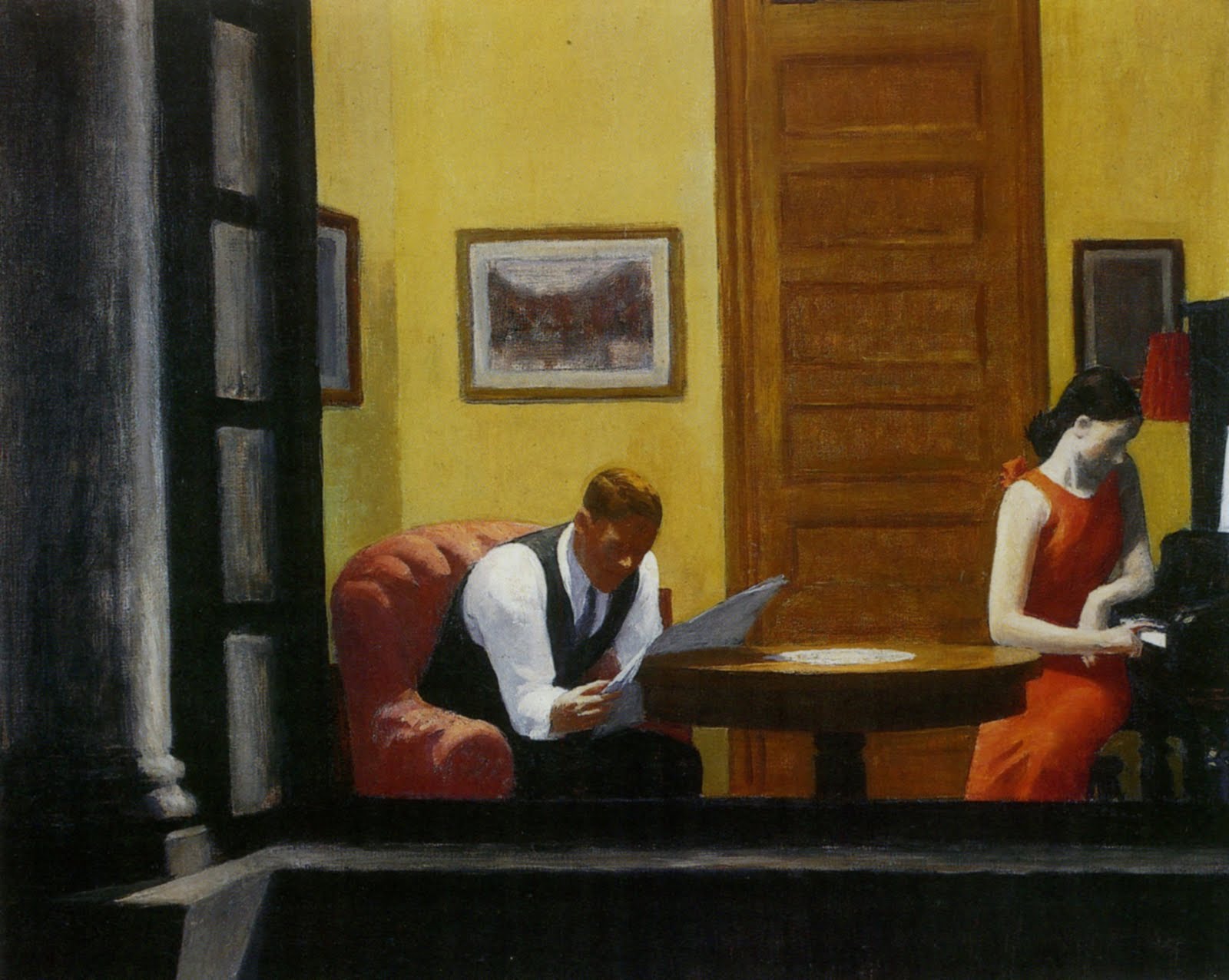

Hopper excelled in painting, discreetly and from without, people who are outsiders to one another. You imagine him staring from the Second Avenue El as it rattled past the lit brownstone windows, storing the enigmatic snapshots of home and business for later use. These are reconstructed scenes, emotion recollected in tranquility. In Room in New York, 1932, it is night; a man reads a paper at a round table, a woman turns away in her own absorption and boredom, touching the piano keyboard with one finger. They are out of sync, and their distance from each other is figured in the simple act of a woman with a shadowed face sounding a note (or perhaps only thinking about sounding it) to which there will be no response. No doubt Hopper saw something like this, yet not very like it. The space would not have been measured by his three exact and conscious patches of red: the armchair, the woman's dress, the lampshade. The figures would have been remote. In the picture they are large, and we are close to them, outside their window. You don't for a moment imagine Hopper on a scaffold outside the window or spying on the couple through a long lens. And yet the painting does evoke the pleasure, common to bird and people watchers, of seeing while being unnoticed; it does put your eye close to the window, several floors up; and this contributes a dreamlike tone to the image, as though you were levitating while the man and woman remained bound by gravity. This is not realism, but the scene is intensely real, a vignette framed in the dark proscenium of the window.

Room in New York

oil on canvas • 74 x 91cm

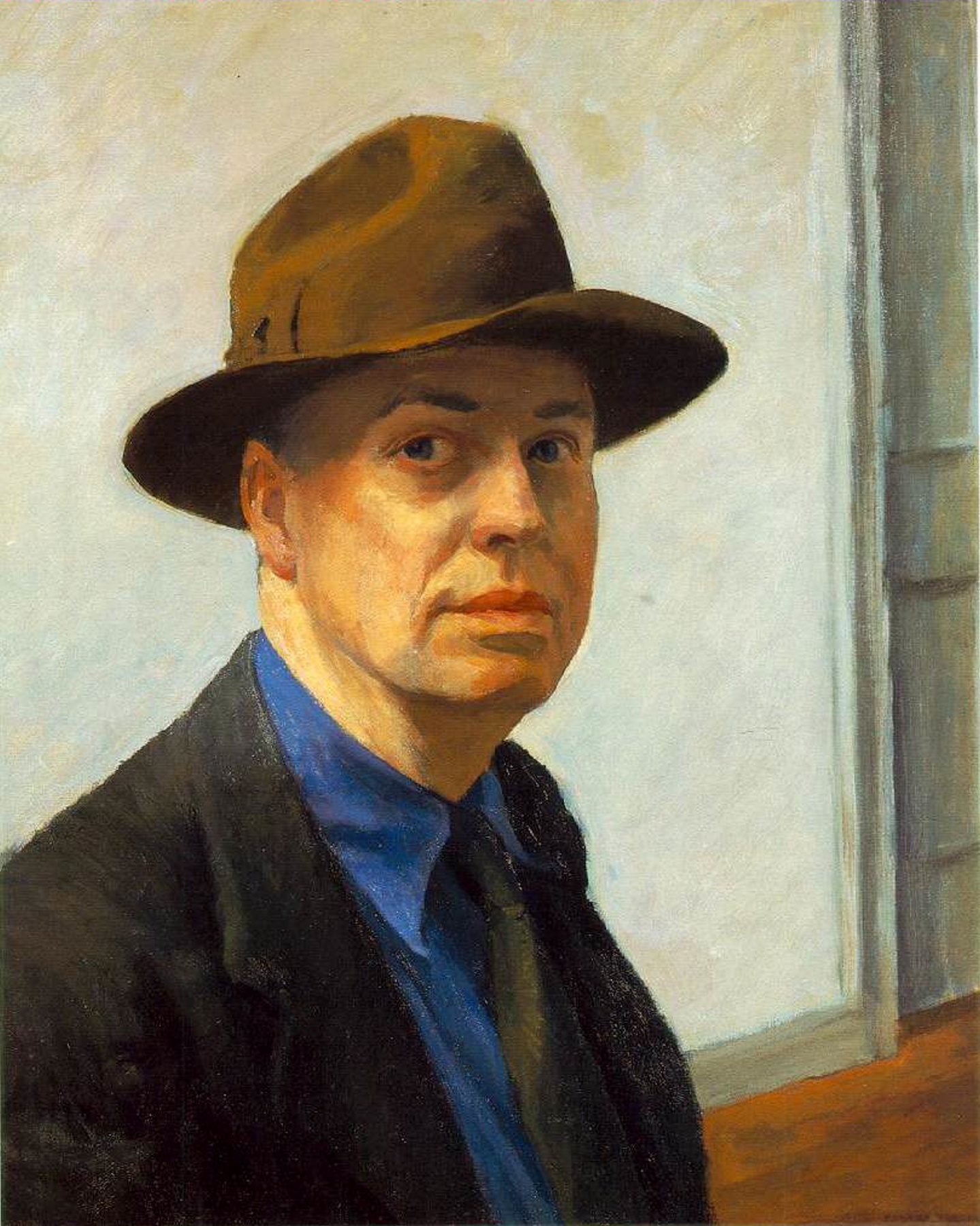

Edward Hopper

Edward Hopper