Previously in Wednesday Thought on Art, we mentioned German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and his romantic approach to art. Today, we want to present more of his philosophy and connection he had with the Symbolists, who claimed: “Suggest, never describe.”

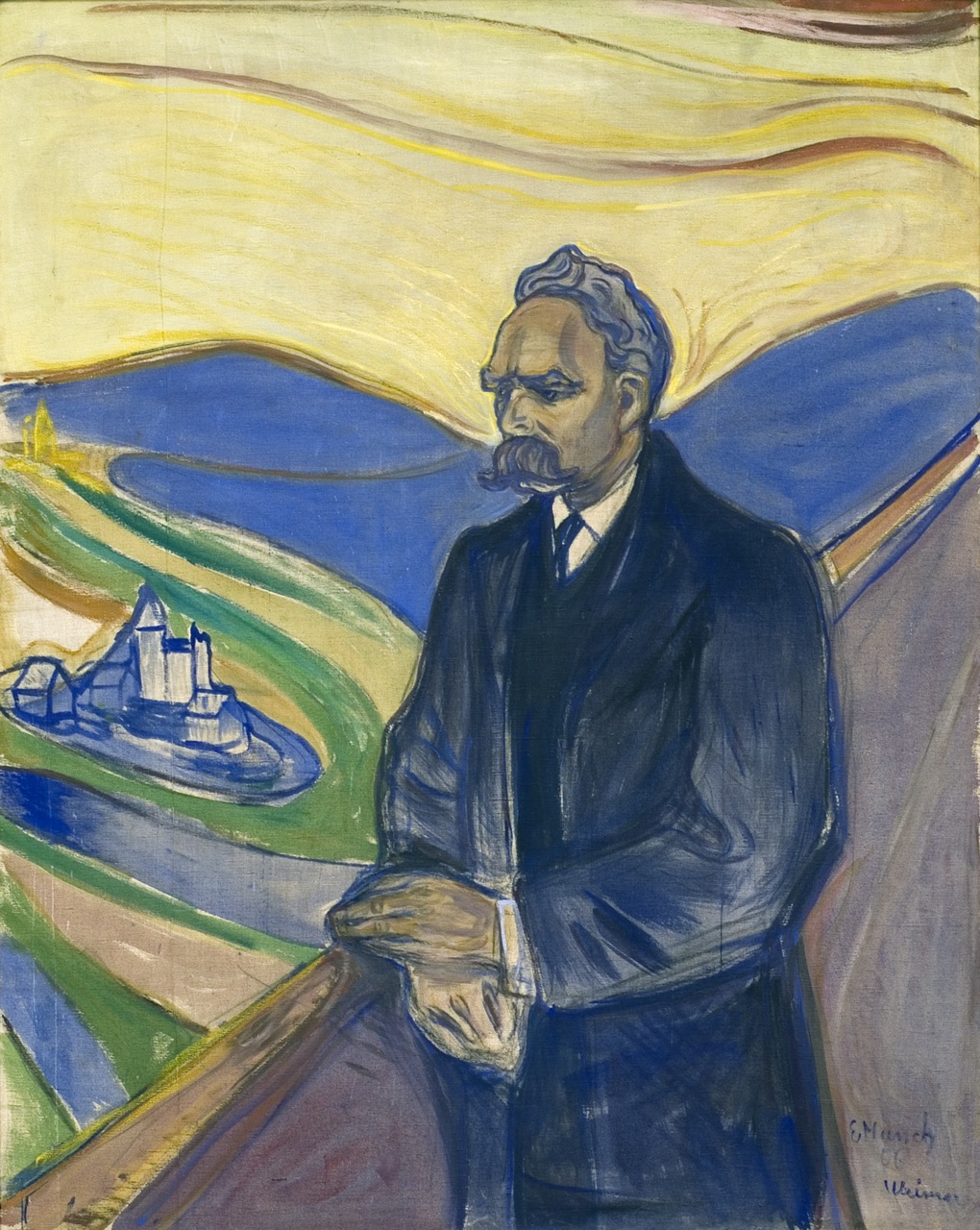

Munch’s portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche offers a unique interpretation of the Symbolist aesthetic as well as Nietzsche’s ideas about art and physiology and the eternal return. The artist first learned of Nietzsche in a series of lectures in Copenhagen and then through the Swedish poet and critic Ola Hansson who popularized German philosophy. Munch began to snap up as many books by Nietzsche as he could find and soon these volumes outnumbered those of his other favorite, Dostoyevsky. Munch received the commission for Nietzsche’s portrait from another enthusiast, Swedish banker Ernest Thiel, who wanted an “ideas portrait” of the great man—the weird thing is, Munch never met Nietzsche in person but he knew his sister and painted this portrait with the help of photographs.

In Nietzsche, Munch discovered a shared spiritual kinship—they both suffered from loneliness, a lack of recognition, and a fear of madness. Nietzsche’s own work on art and physiology coincided perfectly with Munch’s temperament and artistic interests; both regarded patho-physiology as a revelatory state, one to be feared as much as sought after. Art and physiology was much on the minds of 19th-century French and German thinkers, who often looked to rationalize man’s place in the world through the burgeoning field of what we today would call “metrics.” With these graphical representations of bodily circumstances, thinkers like Nietzsche and Munch believed that elusive concepts like being, beauty, and aesthetics could be captured and made manifest, a sort of grand interdisciplinary ontological experiment. Munch also found Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return sympathetic to his aims as an artist. “From my rotting body,” Munch moodily intoned, “flowers shall grow and I am in them and that is eternity.”

The constant dialectic taking place between material artistic genius and an intuitive metaphysics echoes Nietzsche in Thus Spoke Zarathustra—“that long weird lane, must we not eternally return?”—and in The Convalescent—“Everthing goeth, everything returneth, eternally rolleth the wheel of existence.” Interestingly, Nietzsche’s eternal return makes no allowance for the soul or immortality, something that Munch, son of a religious military doctor, could never quite reject: “One must believe in immortality.”

Edvard Munch

Edvard Munch