A couple of weeks ago I showed how Muybridge used his camera to deconstruct motion. He deconstructed motion into stillness, proving a horse could hover above the soil for a moment. This was a scientific breakthrough, as were many photographs of the time. By that time Rudolf Koppitz had just begun his career as photographer in 1902—new directions were sought which became known by a new name: secession.

Rudolf Koppitz was born in 1884 near Freudental, Upper and Lower Silesia (today Skrbovice in the Czech Republic). From very early on he was interested in photography, and, after studying it, became an apprentice and then a recognized professional at the age of 17. By 1908 Koppitz began to have some time to make his own photographs, taking rather traditional images of traditional subject matter. His career was halted when he was drafted in the First World War, becoming a “master assistant for field photography”. Assigned to take aerial photographs of the battlefront in the East, he created sharp geometric, almost romantic, images, clearly marking him out as different from other photographers.

The photo shown today dates from his next period. It comes from a series studying human form and motion, Bewegungsstudie no.1. Showing a new form and no longer deconstructing motion but constructing rhythm and patterns, it is almost an attempt to make stillness into motion. The three ladies in the background show their heads and feet only, forming a left-curve-right motion. Their bodies have become a black background for the nude lady in front, the direction of their gaze moving down, while the form of their feet suggests a ballet-like movement to the left. They seem to contrast and complement the nude lady, who arches, looking disengaged the other way. Her nudity and motion is in complete contrast to the background ladies.

Being attached to the principles of naturism, Koppitz was looking for nature and physical exercise. We see the tension in her muscles and her right arm slightly moving up in contrast, yet further enhancing the line of the background ladies. Her hair hangs loose, forming yet another contrast with the background ladies.

Koppitz’s aesthetic vocabulary was adopted by the Austro-fascist powers and the supporters of National Socialism. We don't know what he thought though, because he died two years before the Anschluss. His wife Anna, however, associated her own work and some of her husband's work with the Nazi purposes, damaging her husband's name. As there is no evidence for his opinion we can rest with the 'not guilty until proven' maxim. He created very special, artistic, and aesthetic photos. - Erik

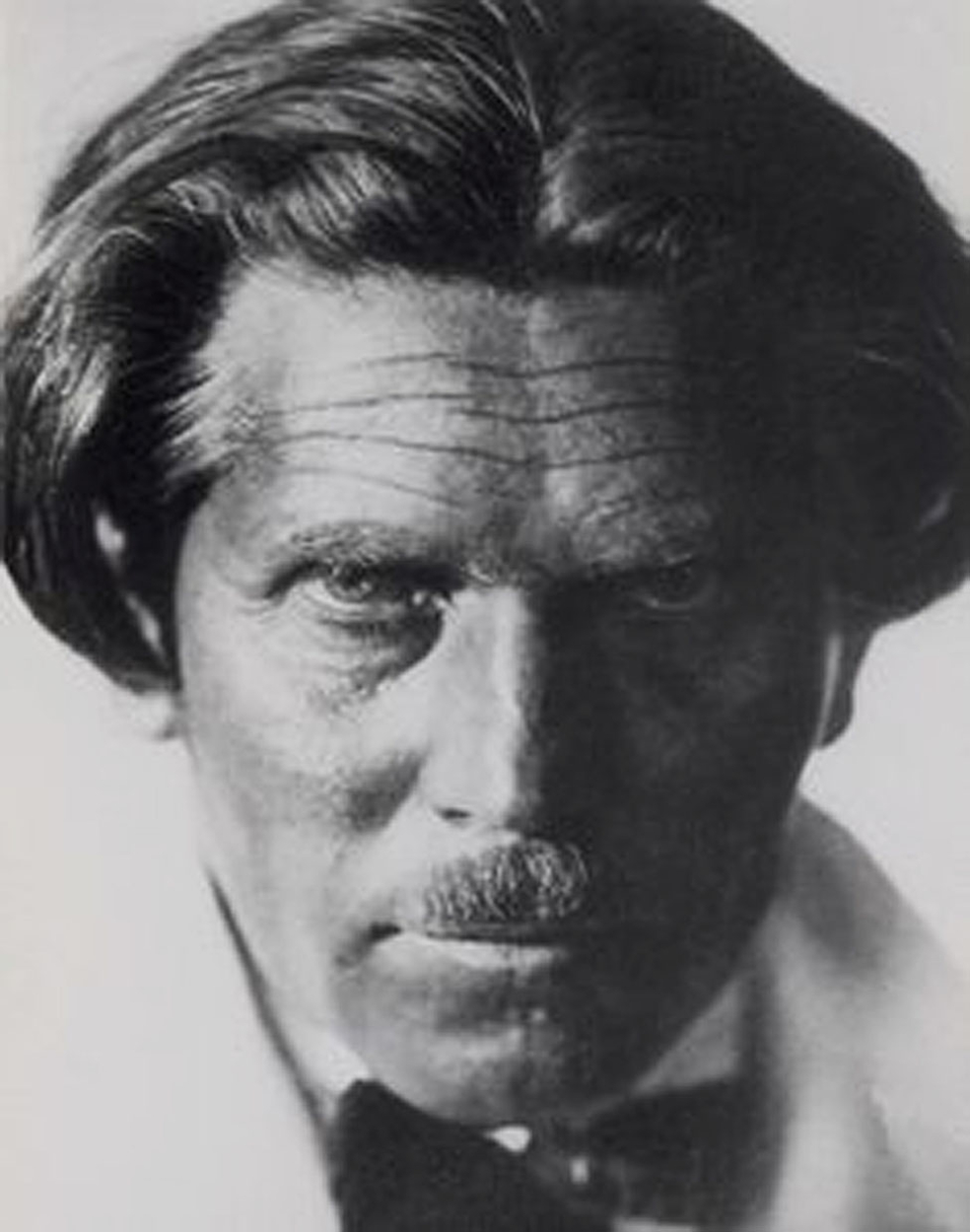

Rudolf Koppitz

Rudolf Koppitz