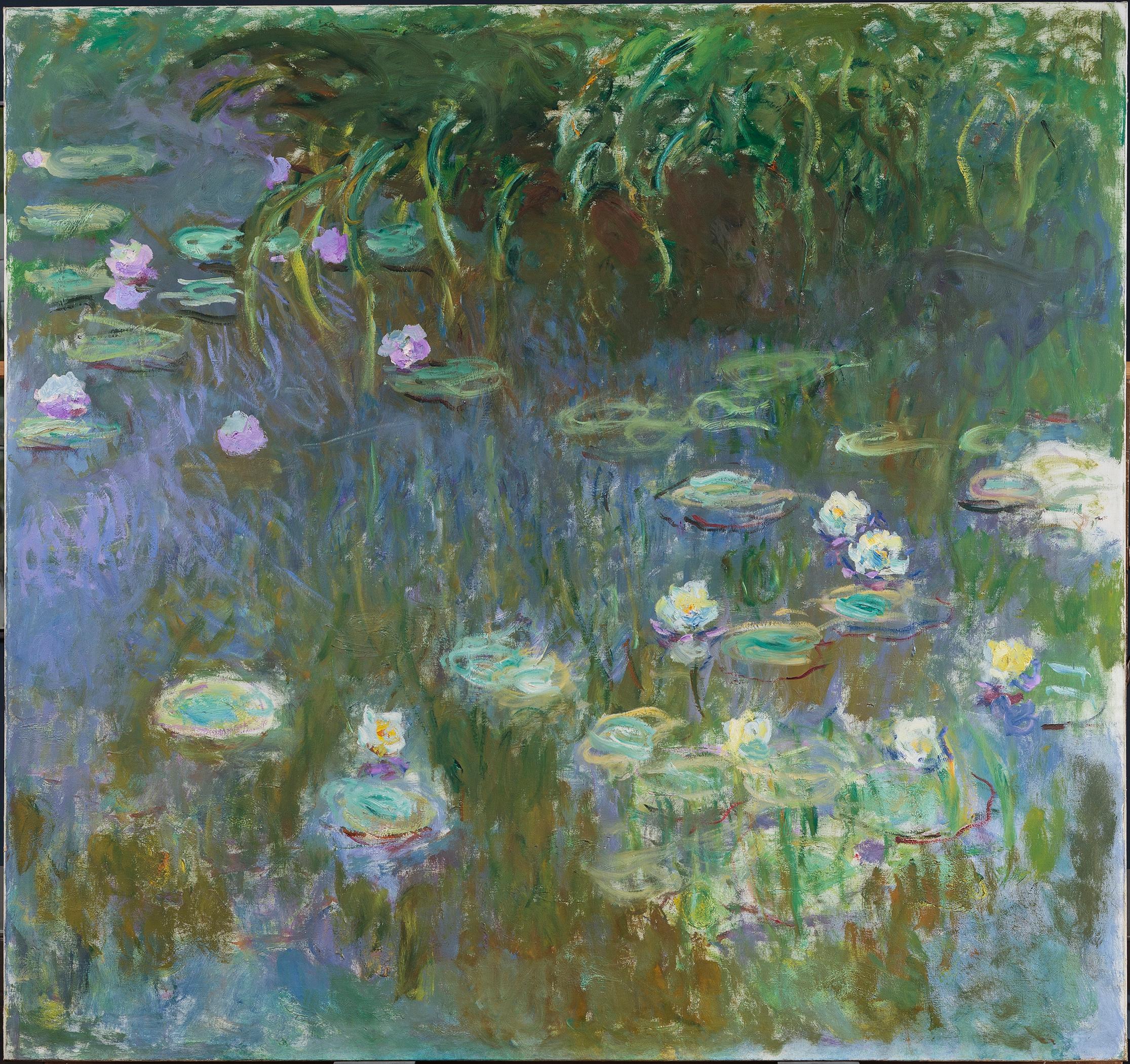

During the last thirty years of his life, Claude Monet made his water garden at Giverny, forty miles from Paris, his principal artistic theme and his final retreat from the world into a tranquil realm of meditation, reverie, and peace. With closely coordinated colors, bold calligraphic brushstrokes throughout this canvas establish intricate sequences of quivering movements across the picture surface. Visual expectations are confounded as Monet turned the world upside-down by placing ground and grasses along the top instead of at the bottom. He blurred distinctions between water, land, lilies, and reflections, making nature appear as something insubstantial, floating, suspended without gravity or depth, in ceaseless shimmering motion—a natural development from his earlier Impressionistic style of capturing fugitive light. As Monet remarked to a critic in 1909, his image of the water garden "evokes in you the idea of the infinite; you experience there, as in microcosm… the instability of the universe which transforms itself at every moment before our eyes."

During the summer of 1914, Monet finally realized his dream of making his water garden the subject of a grand decorative scheme, a project that was to consume the remaining twelve years of his life. He worked out his epic concept on huge canvases that convey the effects of varying light conditions on the pond during different times of day. Painted as a gift to the French nation, these vast decorations are housed in two large oval rooms in the Orangerie des Tuileries in Paris. The compositional features and unusual size of the Toledo painting suggest that it was conceived as a new half-width canvas for the right side of a triptych entitled Morning, but then rejected by the artist. It was left unfinished in Monet's studio at his death.

Claude Monet

Claude Monet