#stopbullying

The name of the girl from this painting is Eugenia. She is not like any other famous girls from art history. She doesn't smile, nor seduce the viewer. She is not rich or noble, even though her dress may suggest that. She was painted because, for the people in her environment, she was perceived to be a monster.

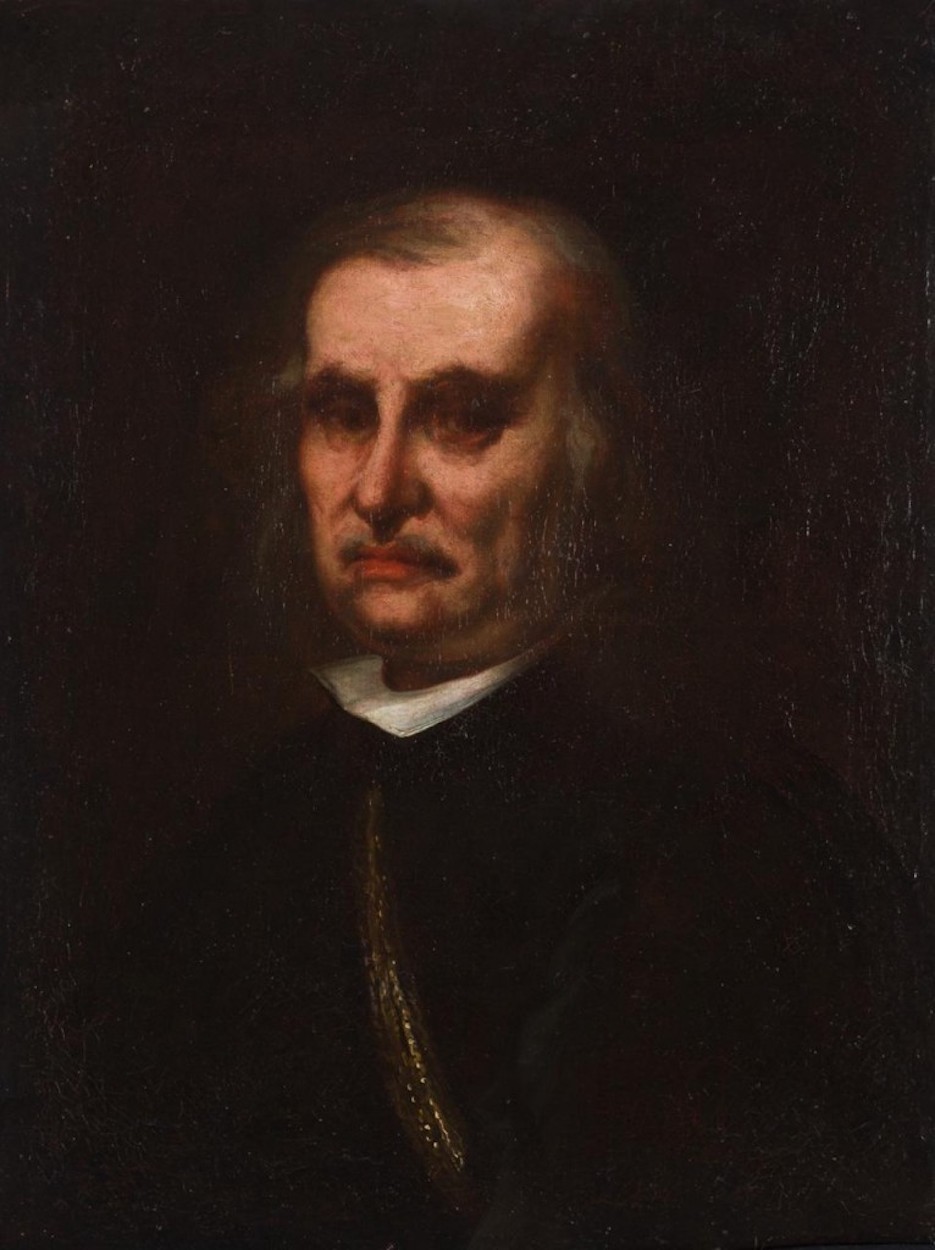

In the courts of Spain´s nobility, the 16th-century fascination with oddities of the natural world persisted into the 17th and was manifested in, among other things, an interest in people with some mental or physical anomaly. Such people were employed for the entertainment of the powerful and were also frequently represented in paintings. Two works by Juan Carreño de Miranda are striking examples of this fascination and attest to the different roles painting has played in earlier historical periods. Both paintings represent a six-year-old girl, known as La Monstrua, whose extraordinary size (she weighed nearly 70 kilograms or about 154 pounds) caused a sensation in Madrid when she was taken there in 1680. It has been speculated that her obesity was the result of a hormonal disorder such as Cushing syndrome or hypercorticism. Of the two paintings, this one shows her dressed, while in the other she is nude.

In them, the deformity is presented in ways that today would strike us as cruel, but that was wholly consonant with contemporary mores regarding the difference. Not only are we contemplating an image of a young girl exhibited like a natural history specimen, clothed and nude (all the more remarkable when we consider the highly restrictive cultural attitudes towards any sort of female nudity during this period), but we are also viewing a play of appearances, much in keeping with contemporary taste. With her nudity exposing her corpulence, and with grapes in her hand and adorning her head, she transforms into Bacchus; clothed, her luxurious, scarlet dress creates an intended contrast with her physical form, making her nude portrait all the more explicit.

P.S. There are many controversial themes in art history and the general attitude towards some phenomena has been changing gradually during the last few years. Read here about the new way of interpreting Medusa in art, especially in light of the #MeToo discussion.

Juan Carreño de Miranda

Juan Carreño de Miranda