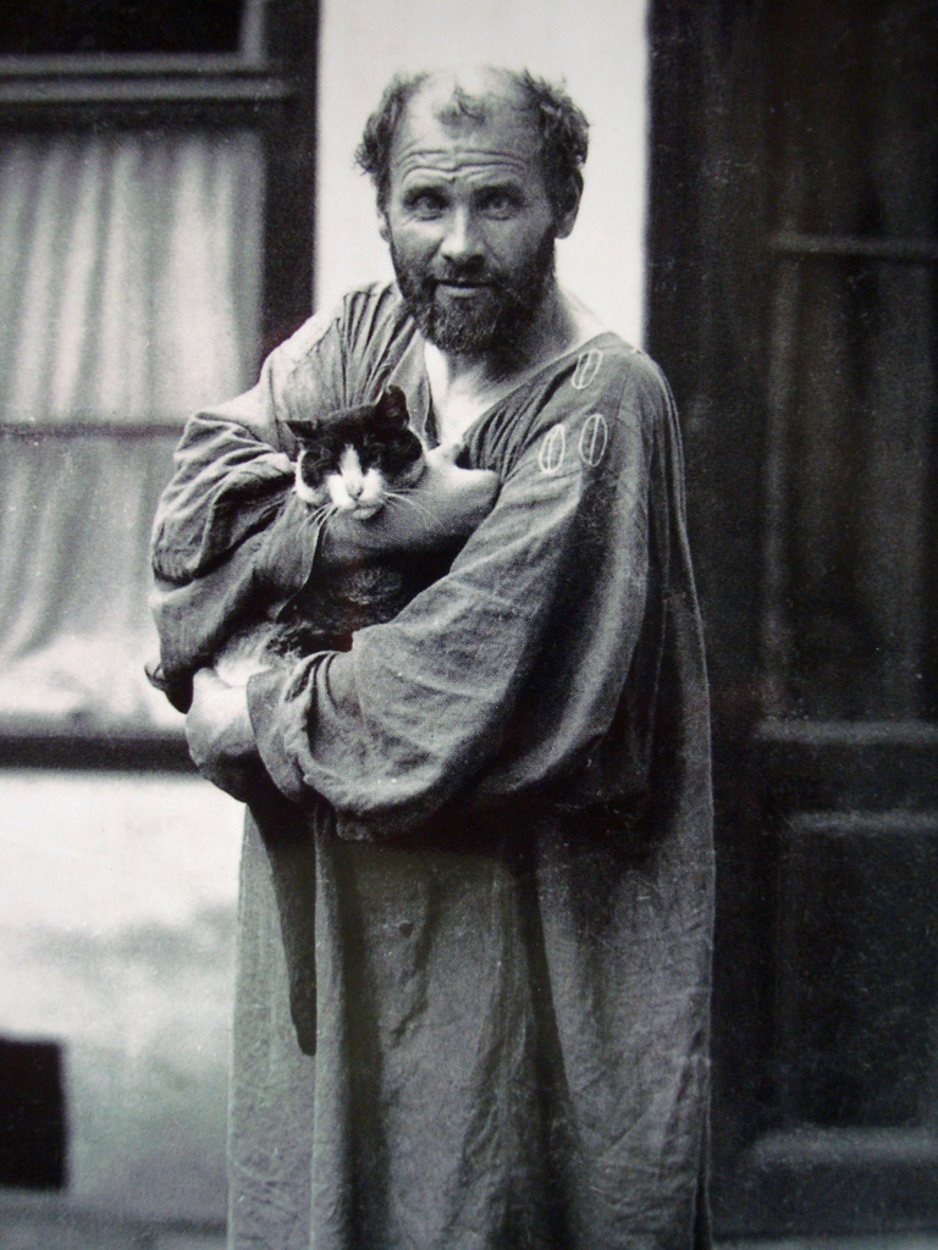

Though long, this story is so interesting that we must write about it. Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer is an imposing and dazzling work that reflects the power, elegance, and confidence of early 20th-century Vienna’s high society. These qualities are revealed overtly and subtly, such as in the sitter’s calm, self-assured expression and in the semi-hidden symbols surrounding her. It is not as well known as other Klimt portraits of women (like Adele Bloch-Bauer) only because it is held in a private collection.

The portrait not only celebrates Vienna’s cultural and commercial elite but also serves as an unintentional epitaph of a world that would soon vanish. The portrait also underscores the Lederer family’s immense power. This family was the second most wealthy in Vienna after the Rothschilds. If you look closely at the sitter’s robe, you’ll notice two light blue dragons emerging from crested waves. These symbols indicate that Elisabeth is wearing an emperor’s cloak. While Klimt often used Oriental motifs in his work, this is the only portrait with imperial iconography, highlighting the significance of Elisabeth and her family.

In the case of Elisabeth's portrait, the historical context surrounding the work offers a new perspective on Klimt and his subjects, contrasting with the painting’s initial tone. It is tragically ironic that a work filled with life, light, and optimism depicts a young woman whose life would take a devastating turn within 15 years. After her father died in 1936 and the Nazi annexation of Austria in 1938, Elisabeth’s once charmed life descended into tragedy. In 1939, the Nazis looted the Lederer art collection, leaving behind only family portraits, which were deemed “too Jewish” to steal. Elisabeth, who had converted to Protestantism after marrying Wolfgang von Bachofen-Echt in 1921, became Jewish again after their divorce in 1934. Elisabeth was left all alone in Vienna: her husband had divorced her, her only child had died, and her mother had fled to Budapest.

Facing likely persecution, Elisabeth circulated the story that Klimt, a non-Jewish artist who had died in 1918, was her biological father. Although this claim is generally dismissed today, some aspects—Klimt’s reputation as a philanderer, his obsessive dedication to painting Elisabeth, and Elisabeth’s own standing as a sculptor—lent credibility to the story. Her mother, Szerena, even signed an affidavit confirming Klimt’s paternity to save her daughter. The strategy worked: Elisabeth received a document from the Nazi regime recognizing her as Klimt’s descendant, and, with help from a former brother-in-law who was a high-ranking Nazi official, she was able to live unscathed in Vienna until she died in 1944.

P.S. Christmas is just around the corner, are you ready with your Christmas gifts? If not, please check our beautiful artsy products in the DailyArt Shop. You will find there something special for Klimt fans. :)

P.P.S. Gustav Klimt painted many iconic portraits throughout his career. Known for his characteristic style, he also made very traditional works early in his career. Discover Klimt's unknown portraits you would never guess were his!

Gustav Klimt

Gustav Klimt