Caravaggio created one of his most admired altarpieces, The Entombment of Christ, in 1603–1604 for the second chapel on the right in Santa Maria in Vallicella (the Chiesa Nuova), a church built for the Oratory of Saint Philip Neri. A copy of the painting is now in the chapel, and the original is in the Vatican Pinacoteca. The painting has been copied by artists as diverse as Rubens, Fragonard, Géricault and Cézanne. This counter-reformation painting – with a diagonal cascade of mourners and cadaver-bearers descending to the limp, dead Christ and the bare stone – is not a moment of transfiguration, but of mourning. As the viewer's eye descends from the gloom there is, too, a descent from the hysteria of Mary of Clopas through subdued emotion to death as the final emotional silencing. Unlike the gored post-crucifixion Jesus in morbid Spanish displays, Italian Christs die generally bloodlessly, and slump in a geometrically challenging display. As if emphasizing the dead Christ's inability to feel pain, a hand enters the wound at his side. His body is one of a muscled, veined, thick-limbed laborer rather than the usual, bony-thin depiction. Two men carry the body. John the Evangelist, identified only by his youthful appearance and red cloak supports the dead Christ on his right knee and with his right arm, inadvertently opening the wound. Nicodemus grasps the knees in his arms, with his feet planted at the edge of the slab. Caravaggio balances the stable, dignified position of the body and the unstable exertions of the bearers. While faces are important in painting generally, in Caravaggio it is important always to note where the arms are pointing. Skyward in The Conversion of Saint Paul on the Road to Damascus, towards Levi in The Calling of Saint Matthew. Here, the dead God's fallen arm and immaculate shroud touch stone; the grieving Mary Magdalene gesticulates to Heaven. In some ways, that was the message of Christ: God come to earth, and mankind reconciled with the heavens. As usual, even with his works of highest devotion, Caravaggio never fails to ground himself. Tradition held that the Virgin Mary be depicted as eternally young, but here Caravaggio paints the Virgin as an old woman. The figure of the Virgin Mary is also partially obscured behind John; we see her in the robes of a nun and her arms are held out to her side, imitating the line of the stone they stand upon. Her right hand hovers above his head as if she is reaching out to touch him. The other figures were identified by Bellori as "Marys" could be Mary Magdalene and "the other Mary". The left figure imitates the costume from Caravaggio's Penitent Magdalene; the right figure reminds us of his Mary in Conversion of the Magdalene. Andrew Graham-Dixon asserts that these figures were modelled by Fillide Melandroni, a frequent model in his works and about 22 years old at the time.

The Entombment of Christ

oil on canvas • 300 cm × 203 cm

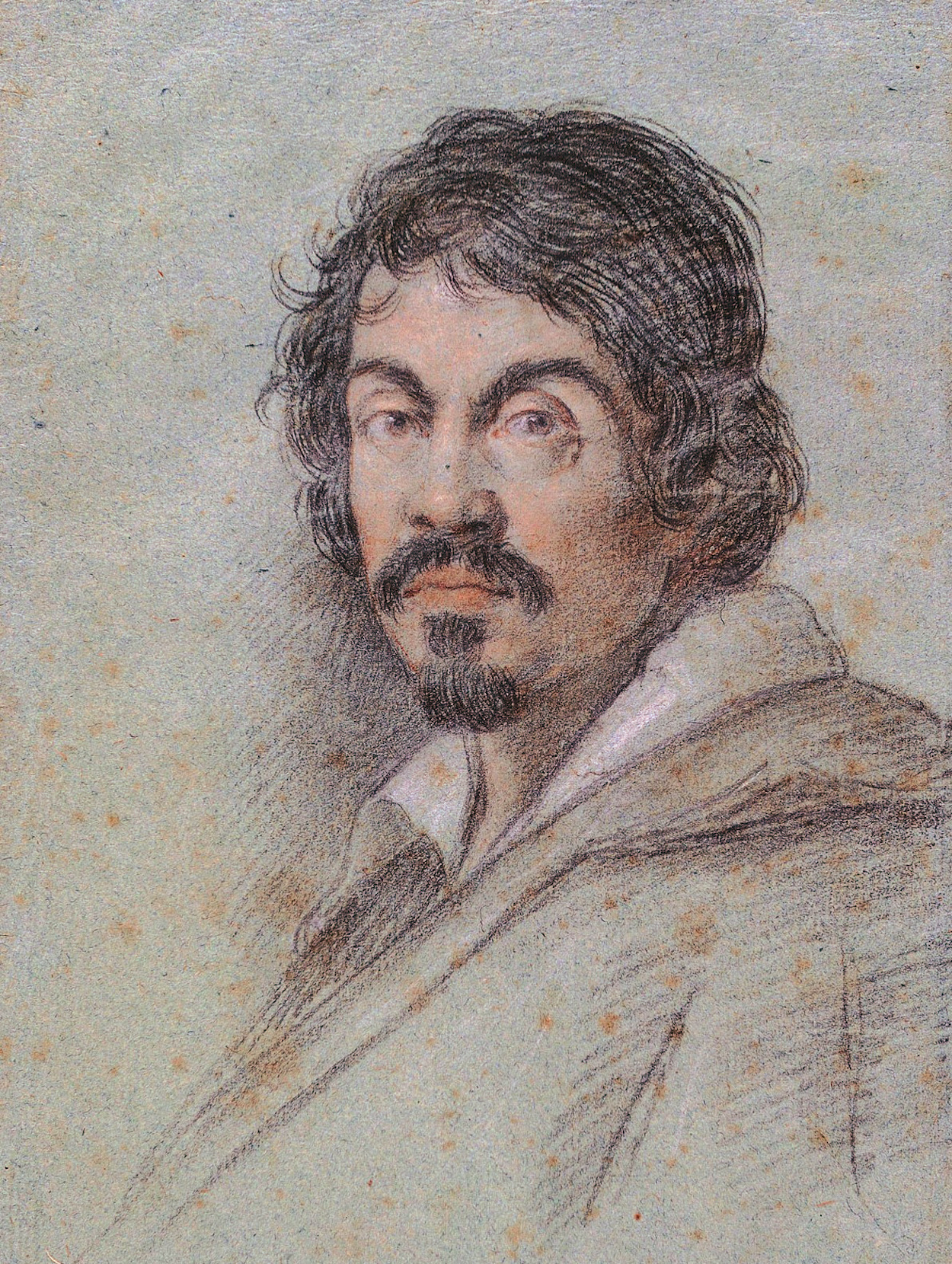

Caravaggio

Caravaggio