Red House depicts a strong, front-facing red house set in a wilderness. The house has no detail except for three chimneys on the shallow black roof. There are no windows or doors, implying no way in and no way out. The house is central, occupying a space almost perfectly in the middle. Horizontal stripes represent land and sky. The landscape itself is featureless but its purpose is important: without it the house would have no sense of dimension and no solid presence, becoming nothing more than an arbitrary flat shape. Instead, because it is set in this ground, the house is able to draw all attention to it. The red shape is a challenge, its straight lines providing a scaffold for a stoic, self-controlled exterior, yet it worries the viewer. The lack of architectural openings breeds a feeling of uneasiness; there is implied secrecy and untrustworthiness in this prominent red face and it stands unmoving and unyielding, facing us with directness and confidence that surprises and alarms.

Malevich found himself in the 1930s staring into the blind face of this unsympathetic ‘red house’, a leviathan on the Russian political and artistic landscape. The creative freedom of the individual was becoming more and more oppressed. Modernist movements—the Constructivists and Suprematists in particular—in which Malevich had been involved, were considered to be inappropriate and the message from Stalin’s new Diktat was clear: obey the rules or face the penalty. The red house is monolithic and inflexible—a powerful symbol of the new red government—but I like to think that Malevich was subverting authority with this painting. Despite the enforced removal of artistic freedom under the new regime, Red House maintains autonomy through implicit meaning. Its ambiguity is the key: maybe outwardly it represents the might of a new Russia, but underneath this obvious exterior is a show of integrity on the part of the artist who is saying, “I stand upright, even if alone. Beneath this façade lies a truthful, autonomous individual rather than a servant of totalitarianism.”

- Sarah Mills

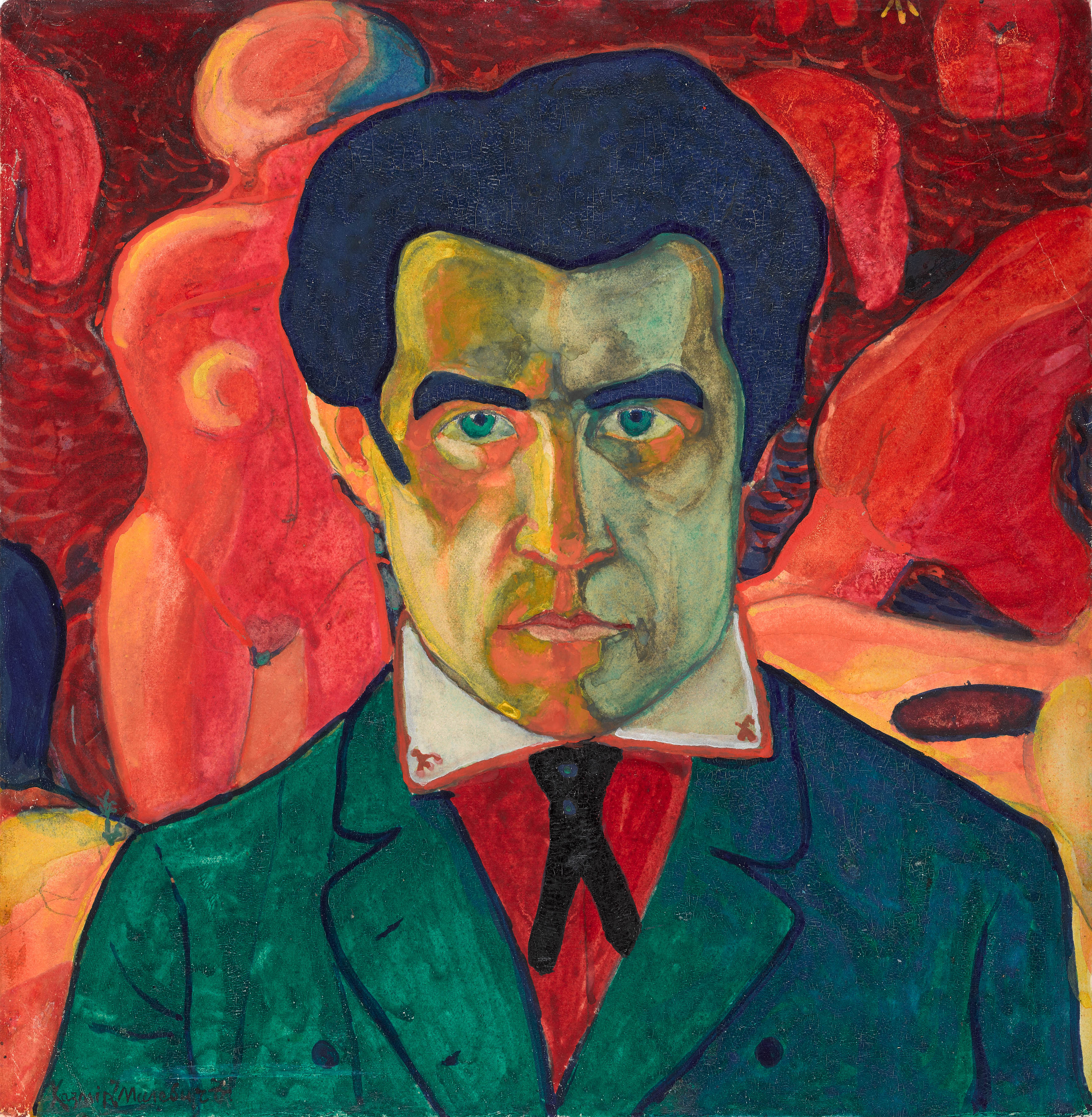

Kazimir Malevich

Kazimir Malevich