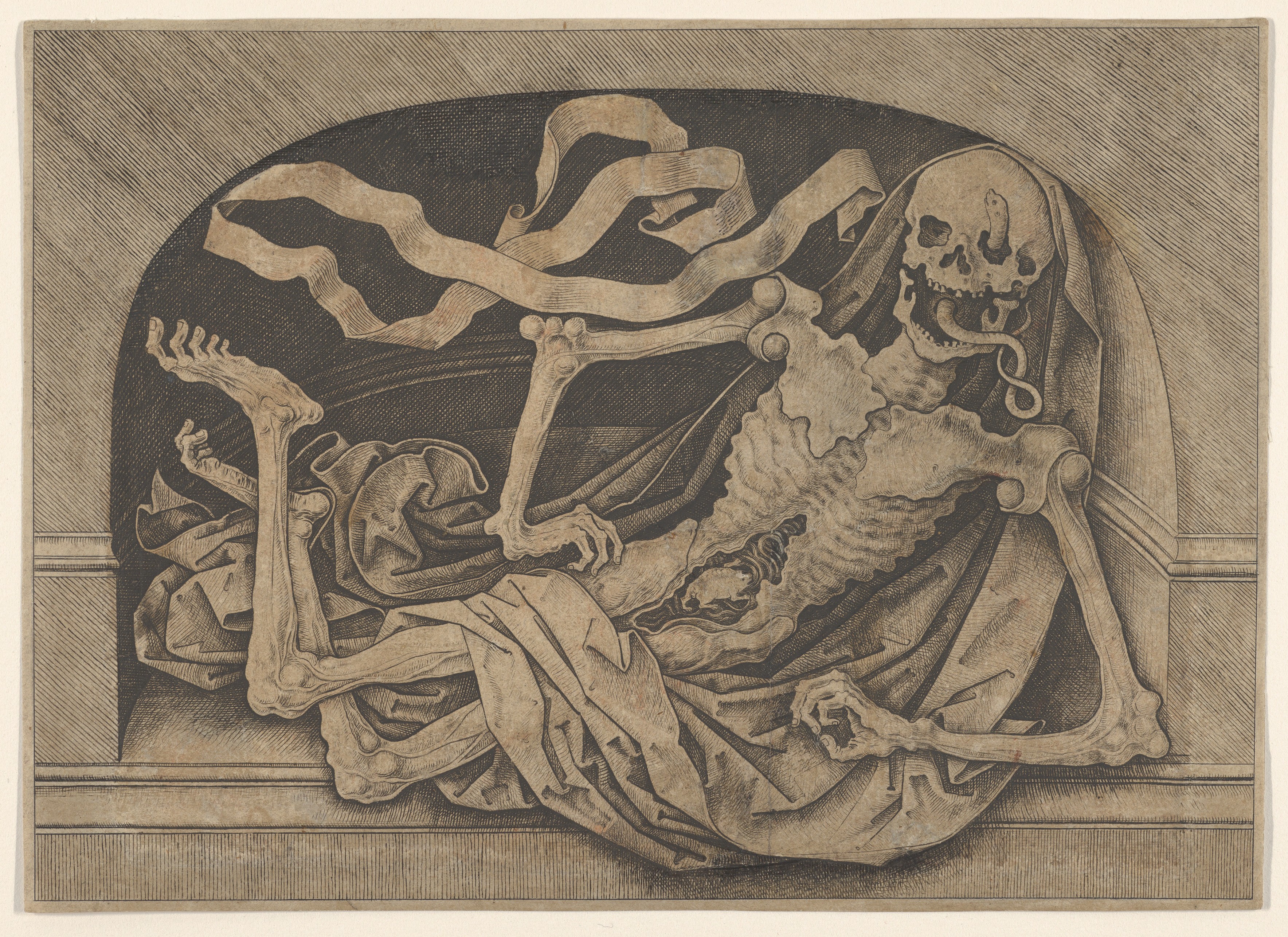

First impressions: Horrible! Deathly! Disgusting? The trick to appreciating this piece lies in getting inside the Renaissance mind, and to do that we only have to ask why anyone would want to look at such an image to begin with.

The Christian religion formed a core part of Renaissance life and was everywhere in the art of the period: representations of Christ, the Virgin or any of a multitude saints filled paintings, architecture, altarpieces and manuscripts. Images were also concerned with the afterlife, and we can see reminders in art of the transience of life, and the importance of living justly in order to earn acceptance into Heaven afterwards. In the Renaissance mind this awareness of death and the need to prepare in life for what came afterwards was paramount, but not at all extraordinary.

Printed images such as the ones that would have been made from this Netherlandish engraving highlight concerns with inner spiritual life. We notice first the proliferation of skulls that confronts us with the subject at hand: the inevitability of death. The scene is set inside a gothic, vaulted tomb where a body is decaying to bones at the bottom. A snake - a symbol of evil in Christian art - makes it way through the orifices of the skull, warning against sin. The posture of the body is haphazard and the shroud is crumpled because decay has caused it to fall away over time, revealing the grisly body. Above the corpse is the figure of Moses holding up the Ten Commandments. There are various inscriptions in the image which, according to the British Museum, ‘reinforce the central theme’ of living a pious and thoughtful life in order to die well.

Engravings could be printed in large quantities meaning that this image would have been quite widely available and relatively affordable, and its production therefore uncovers deep-set religious values invested in art that expresses a need to consider life’s journey and its uncertainties, and which gives a sense of purpose to something that is ultimately easily broken. Mortality, death and decay were an intrinsic - and unavoidable - part of daily life: it was important to gaze into the sockets of a skull whilst contemplating this because it returned meaningful messages to do so.

Our reaction to this image might say quite a lot about modern life too: contemplation upon skulls and mortality? No thanks! However just because we don’t always actively seek these subjects out doesn’t make us sheltered from them: we need only to face our own experiences or read the news to know that these themes haven’t changed much. In this way we are very much linked to our Renaissance predecessors even though they are hundreds of years away.

- Sarah

Master IAM of Zwolle

Master IAM of Zwolle